Booksellers make money because our mental, physical and behavioural similarities outweigh our differences by a wide margin. A novel and its characters can appeal to many different people, even if those readers outwardly present as (and usually insist on) being very different with regard to only a few specific traits - be that skin colour, gender, sexual orientation, political affiliation, or whatever else is thought worthy of individual distinction, attention or often deliberate, rancorous and unnecessary division.

“The vast majority of variation occurs within groups;

very little variation differentiates between groups.”

This statistical surety which marketing folks rely on is similar to how most genetic variation occurs within populations, not between them, no matter if you define a population by geography, ancestry, race or any other measure. We are far (99.9% far) more similar to each other than we care to admit.

Booksellers know this. And so do authors. But a specific group of contemporary, self-enlightened readers? Not so much. They like being different. Different is good. It’s tribal; it’s partisan; it can help them stand out in any madding, media-obsessed crowd.

But there’s now a difference emerging that every previous blossoming of kidulthood didn’t exhibit. They want their ubiquitous ‘uniqueness’ to be stretched across everything they do, see, hear and read. And they want the people who help make that difference so very real to them, to also live it in thought, word and deed. They want their bubble to be an all consuming closed loop of recyclable safe space. The fact that there are millions of such bubbles, all overlapping by 99%, all jostling to join the ever lengthening – eventually meaningless – acronyms of inclusivity, doesn’t enter into their reasoning.

This could be seen as a writer’s nightmare, far beyond the usual pen-wringing; a publisher’s impossible conundrum on commercial differentiation; or a panic-stricken PR problem.

But it’s not. The remedy is quite simple…

You apply the science (you have that, right?). You do the sums (a spreadsheet is fine). Then, as an aggregated assault on concerted lunacy, everyone who wants to, without fear or favour, should simply whisper in communal chorus: ‘I think to fuck off would be best’.

Do it quietly. Without a fuss. Both you and them. Because you still can, even if they might struggle. Because it might just work, as long as they stay glued to a screen and don’t turn into phone-free hermits. Which they won’t.

You’re no doubt shocked. The solution seems so abrupt – if perhaps too trivial, too neat and tidy. So allow me to expand on the problem, it’s likely mechanism and my reasoning…

I think the contrary readership trend to self-identifying via imbibed content can be traced back to the early 20th century, when movies and advertising began to penetrate minds that were being turned into sophisticated, discerning media sucking machines (and if you believe that you’re going to hate or be utterly befuddled by the rest of this piece). It’s when screen-based images initiated a frantic, accelerating injection of neurotransmitters into our brains - ‘just for the thrill of it’, or ‘because I want to’, or, more ominously, ‘I can’t help it’.

As movies caught up with our capacity for imagination, tying us ever more tightly into what we wanted to experience, I believe this was also when people started to identify themselves in books (and as lawyers mined ever deeper profits from defamatory accusations). Our brains were becoming much better at bringing perceived fiction into a closer state of reality. This trend has deepened, with the graphical supplanting the textual (manga is some booksellers’ unlikely saviour), PoVs shifting to first person in books and games, and, in the near future, cumbersome personal screens evolving into retinal-projected scenes.

Our brains started getting much better at bringing fiction closer to a state of reality.

Now there’s a relatively new trend on the book marketing block: ‘lived experience’. In itself, this concept isn’t new, but a more invidious application of its principles has recently been let loose on the writing world. This variant results from the following recipe:

Take an unhealthy dose of American campus-fed identity politics.

Add a long-simmering portion of the previously discussed mode of self-identification from images manifesting inside a reader’s head.

Stir thoroughly in a large social media pot, seasoning with echo-chamber or self-verified sauce.

Reflect this mix back onto the target work’s original author (preferably whilst alive).

Serve with oodles of anecdotal n=1 ‘evidence’, willingly spread by those who don’t have a statistical thought in their humanities-laden head.

Those readers who do live through the experience of swallowing copious quantities of this resulting vile, stinking substance will want (above all else, including quality of plot, characterisation or even plain decent writing) to assume an author has done, identifies with or adequately represents how their characters appear and what they say and do on the written page. And if it’s not to their liking, then the shouting, booing and cancelling, plus all other manner of necessary bad stuff can commence. Just as importantly, if an author does write lots of things which they claim to believe in (commercial expediency being a not unknown factor in fictional writing) then they are lauded for their ultra-realistic representation and lived realism, no matter how shit the actual book might be. They are now one of them – and woe betide them if they renege on that implicit pact.

There’s a new trend on the book marketing block called ‘lived experience’.

It means dealing with all kinds of unnecessary bullshit.

Regular application of a ‘lived experience’ filter (by anyone with a vested interest in joining them) means authors assuming responsibility for their characters’ thoughts and deeds via their written words; it means dealing with all kinds of unnecessary bullshit on social media and review sites, at book readings and events; it risks authors being labelled as weirdos, pariahs and every kind of ‘-ist’ imaginable. But far, far worse, it also threatens books with becoming irredeemably and indescribably dull.

This is because some vocal readers unfortunately fail to distinguish fiction from reality (or, far worse, consciously deny any difference). Being steeped in a cultural milieu which rewards red-flagging, declamatory shaming and individualisation by mental and physical struggle means unacceptable characters can only be the product of unacceptable minds. They make no allowance for variety of experience and preference and opinion within their groupthink, it being greater within than without - if only they’d admit it. But, like pirates at a one-legged, eyepatch-only party, no-one is going to check if a leg is folded or a second eyeball sits underneath.

They also fail to see that authors are already a source of potentially unlimited diversity, both within and without the mental imaginings and character constructs they create from unconscious forces still unelucidated by science. You don’t need a dedicated, approved author sat within every one of those bubbles, each one struggling to create something special, only for it to be strangled by ever-changing local obsecessity (Aaghh! A contrived bastard of a word has already sprung from my addled imagination).

These critics will disparage women characters being described by men; of one race being written of by another; of astronauts being described by the earthbound (yes, it logically follows); of food and language being misappropriated (conveniently forgetting the potato chips they ate, the pants they wear and the English they speak). They are wholly blind to themselves and therefore to all others, far more than the proverbial plank and a speck of sawdust.

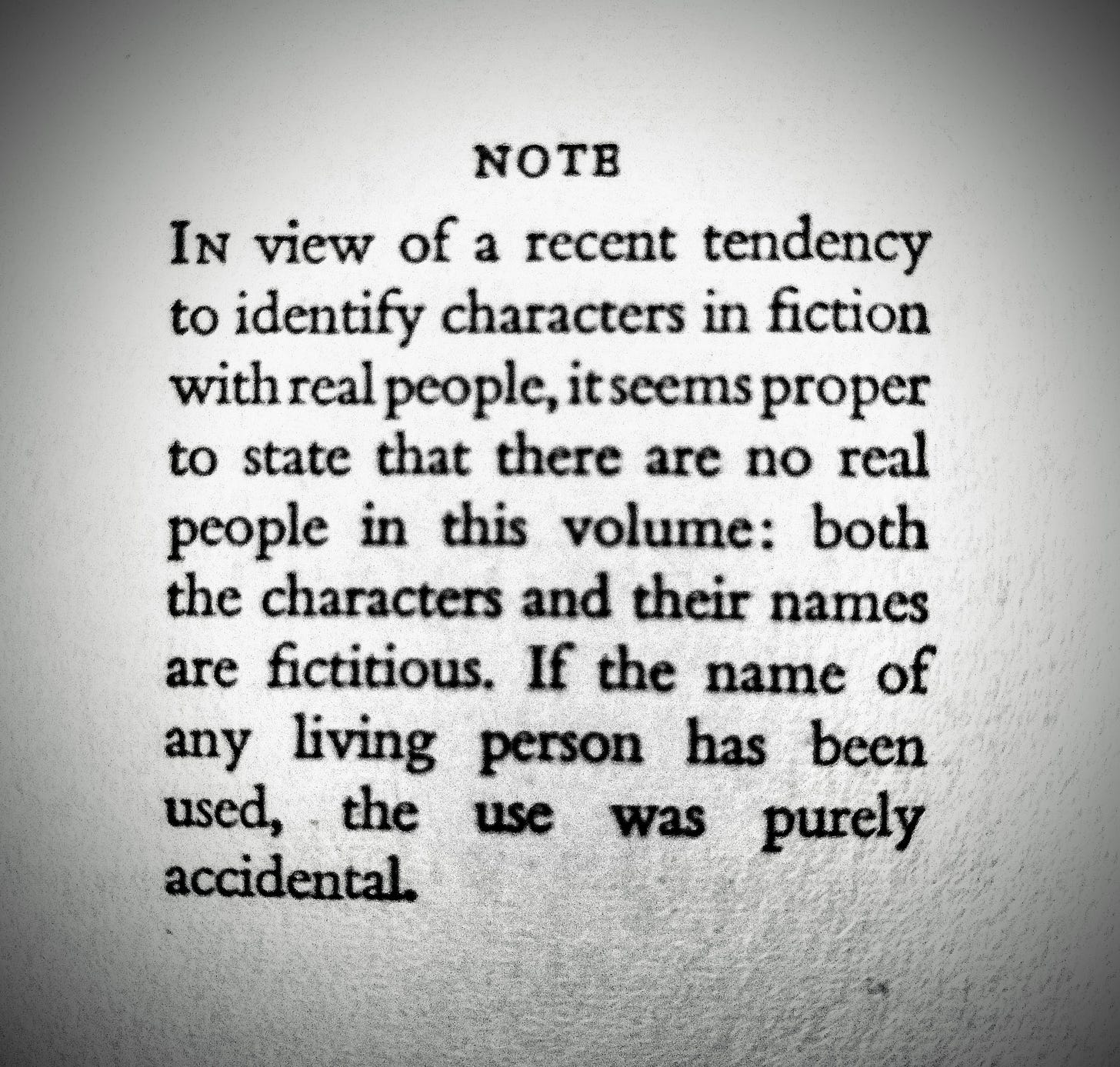

I’ve paraphrased my point below in a very simple manner by rewriting the earlier disclaimer:

“In view of a recent tendency to identify fictional characters with their authors, it seems necessary to state that this book’s author does not inhabit this volume; neither in the characters, their actions or their behaviours. If anything is similar to what the author has, is or will do, then it is purely coincidental or accidental (perhaps providential). We ask you to kindly accept the difference between literary fiction and actual reality or, if you’re still struggling, please fuck off elsewhere.”

Sometimes it’s absolutely necessary to act like a word-gun toting illiberal to ensure your mind stays liberated. And if it wasn’t me saying this, it would only be one of my characters. Because we’re entirely the same, aren’t we?

But, despite all the above, I retain an unerring optimism, because you and I are humans too – and so are they. We all collectively have more in common with each other than with parents, children or any amount of annoying friends or neighbours. So they will eventually understand. This semi-collective, unadulterated madness will pass. I promise.

After vanquishing those fomenting, nascent bubbles of deliberate strife, we’ll soon be creating like we’ve never created before. We’ll be able to erase differences, virtually and physically. What we think and do will be culturally assimilated into an accepting, always feverishly mutating, global content corpus; still as individuals, yet part of a roiling shared consciousness. Unleashed and unlimited, we’ll have tools our early 20th century contemporaries could only imagine – did somehow imagine – despite not owning a telephone, a keyboard or even a streaming subscription. Because they were and remain more like us than we care to admit. Like all humans have been, in essence and as contrarily regarded, throughout the course of our revolving history.

Now, there’s a thing to imagine.