Sometimes you read something which grates on your nerves. Last night an impassioned plea for science fiction writers to read more literary fiction scrolled past my weary eyeballs. A good night’s sleep was not had by all. Because…

It threw me back to my schooldays, when my far younger, but equally fatigued, eyeballs were engaged in an intensive science curriculum for gaining medical school entrance, but I was still being forced to indulge in an English Literature qualification at the behest of a humanities-skewed staff room. In their Two Cultured minds, the literary passions invoked by ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ far surpassed those attained by delving into the spooky mysteries of a quantum-based universe or the mutational perils of a meiotic cleavage. It was not the best of times.

Eventually, after spending the rest of the night and following morning nurturing a peeved, irrational reaction, my brain burst forth with this querulous pustule of self-doubt:

Am I capable of writing over the course of one afternoon some prose which induces strong, albeit mixed, emotions, without invoking tea-sipping aliens, non-baryonic powered wormholes, or a polyamorous space pirate with a breathtaking grasp of zero-gravity swordplay?

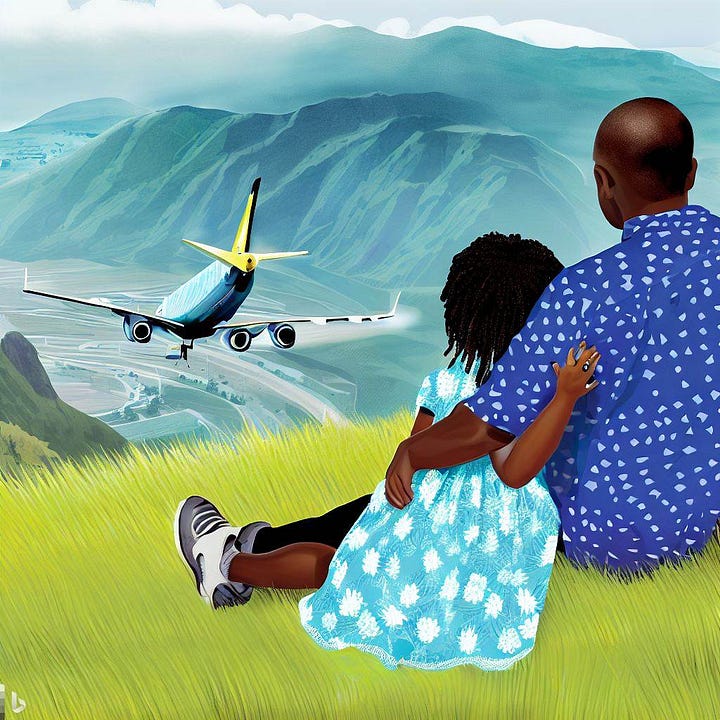

To aid my foolish endeavour, I took a prompt from an interaction I noted and finessed sometime during July 2020 between a father and daughter, as I sat on a hilltop above Bembridge on the Isle of Wight1.

Setting: National Trust Fort, Bembridge, IoW (very close to England).

Original Prompt: A postman who can only see his daughter once a week. She likes to walk on the cliff downs and watch the planes taking off from the small airport in the valley. He drives a battered beige Land Rover. Grizzled grey beard, child wasn't planned, short relationship with mother. She has dark brown, curling hair reaching her shoulders and wears a yellow dress printed with blue flowers.

They disappear down the hill, hand-in-hand. They return with her running ahead of him in the waist high sun-browned grass. She glances back at him, puffing out of breath, calling out questions and observations in a happy voice. But there is another look on his face. A mixture of weariness, from the early rising necessitated by his job, and sadness that his time with his daughter will come to an end all too soon again. Another week in his grimy one bedroom flat before he gets to swing her round by the arms, as she flings her head back and laughs out loud to the heavens.

So here I go again, dear friends, squeezing my words once more unto an inconsequential breach.

Every Sunday morning, he parked his battered beige Land Rover outside her mother's house and waited for his precious daughter to emerge. She was always ready, clutching her backpack and binoculars, wearing her favourite yellow dress printed with big blue flowers. She ran down the garden path, face alight, to hug him tightly, then climbed into the passenger seat and buckled up. His smile was as wide as hers and he ruffled her hair before starting the engine. They pretended to be taking-off in a plane, her favourite beginning to another treasured day together.

He was a postman and only able to see his daughter on Sundays. She’d arrived after a brief, pointless relationship. Her mother had moved in with someone else soon after the birth. They, in turn, had left on her second birthday. He’d wanted that so badly he’d hit them, hard enough so they didn’t return. But he’d never married, never settled down with anyone else. He lived in a grimy one-bedroom flat in the city, spending too many hours at work sorting and delivering mail. He hated his job, but he loved his daughter.

She was ten years old, happy and curious, full of questions and observations. She liked to walk up the steep chalk downs outside the city, holding his hand before cartwheeling back down. And she loved aeroplanes. They would watch them landing and taking off from the small airport in the valley below. She’d look avidly through the binoculars he’d bought for her last birthday, telling him their names and numbers. He would listen and nod, trying to guess where they were flying to and from. Places he’d only seen in the free magazines he’d pushed through other people’s letter boxes.

He knew far more about his daughter than about planes: her favourite colour was purple; her favourite animal was a dolphin; her favourite book was still Harry Potter. He also knew she dreamed of being a pilot when she grew up, of flying away someday, to see the world beyond their limited horizons. Or maybe even become an astronaut, because that meant flying higher – ‘higher even than heaven, Daddy’.

Loving his daughter more than anything else in the world meant an aching sadness which gripped him even when they were together. He knew he was missing out on so much of her life, so many moments and memories he’d never share. Another father figure had appeared in her life, her mother's new husband. He treated her well and bought her the things they said she needed, the things her mother said her father ‘couldn’t possibly afford’. It hurt him when she said she loved him too. He hadn’t asked if she loved him more. He didn’t need her answer. Not now.

He wished he could see her more often, but that had been impossible. There was never enough money, few promotion prospects, very little future. He had nothing to offer his daughter but his love and whatever time he had. But it wasn’t enough.

"Look at that one, Daddy! It's a Boeing 737, flying to Paris!" she exclaimed.

"Wow, that's amazing!" he replied.

"Do you think we could go there someday?" She often asked this.

"One day. Maybe."

"Have you ever been there?" she asked.

"No, love. I haven’t."

"Oh. Have you ever been anywhere else?"

"Not really."

He’d never left the country, only occasionally travelled beyond the city of his birth. He’d never had the chance – and only recently the desire. But he’d been content with his simple life, seeing his daughter every week. Then she began to grow up, to give voice to the impossibilities he’d failed to give her. But she’d also opened his eyes, made him desire more, for the both of them. More than he could ever give. As another plane soared into the sky he felt the urge to tell her, that he wanted so much to fly away with her. Until recently, he’d always rejected the fantasy. He had his place in her life, acknowledged the limited time and world he’d been given to share with her. He was just her postman, a Sunday visitor. A father for a day. Until they’d sent him the appointment letter. Afterwards, the nurse had offered him a cup of tea.

They spent the rest of their day walking along the cliff paths, sitting on a bench, eating the sandwiches he’d made especially, picking at the fruit he insisted she liked. When they returned to the car, she ran ahead of him through the waist–high grass, glancing back as he puffed up the final slope, still asking questions, bubbling over with life. He tried to hide his sadness that their short time together was ending once more, trying to bury the weariness of early morning risings; of spending another miserable week by himself. It remained an eternity before he could once again swing her round by the arms, her head tilted back as she laughed out loud to an infinite corn-blue sky.

They pretended to be in a slower plane on the drive back, but the moment to part still came too soon. When she climbed out, he was waiting on the pavement to hug her tightly, not wanting to let go, whispering that he loved her so much. Yes, of course he’d see her next week, just like normal.

He watched her in the car mirror as he drove away, bobbing on her tiptoes and waving, still smiling, her mother holding her back. He only wiped his tears away after turning out of the street. The radio was playing ‘Feel’. That’s all he wanted: to feel again; to not be dying inside.

When he arrived back at his dreary flat, he didn’t need to think about another tedious week of work, counting the days until Sunday. Next time he saw his daughter would be different. Next time, there’d be a surprise in store for her. Everything he knew they wanted together had been meticulously planned.

He’d saved up enough money to buy two plane tickets to Paris. He’d already quit his job and would pack their suitcases tomorrow. There would be a note left downstairs for his landlord and a letter sent to her mother. For another postman to deliver the news of what he’d done. Of what he’d always wanted to do. What his daughter deserved to have.

His decision had been sealed when they’d said the insurance would pay out. He was going to take her away and show her the world. To be more than just her Sunday visitor. He was going to be a better father, the best he could be, for however long remained to hold on to her. Then, after he’d gone, when he was higher than even her heaven, he’d wait for her to achieve her dreams so they could be together again.

He wouldn’t be her Sunday postman, but her pilot; her rocketman, reflected forever in the bright blue sky of his precious daughter’s eyes.

(1165 words)

Writing Tip #502 : Keep your scrappily scribbled witterings forever. You never know when you might need them.

Well-written story. Excuse me, I have something in my eye.

This one hits hard...